XSS in the AWS Console

June 3, 2021

As I had posted about on Twitter, I had recently started a side project to fuzz the AWS API. This was the logical next step to my previous work on the subject. To support it, I’ve had to build my own library for manually crafting AWS API requests, and mutating them. I think it would have been a very fruitful research path to go down, however I managed to fuzz my way into subscribing to a $36,000 a year service that I couldn’t disable. It eventually got resolved (thank you so much to everyone who helped/offered to help. It was a nerve racking experience), but I’m going to stay away from fuzzing the AWS API for the time being for obvious reasons.

The good news is that before that whole fiasco and even though the library wasn’t even done yet, it had earned itself a bug and this writeup is an explanation of it. It was reported through the AWS vulnerability disclosure program and is now fixed. Thank you to Peter and Patrick from AWS Security for putting up with all my emails!

Discovery

As you can imagine, fuzzing the AWS API is no small task. There are hundreds of AWS services, and thousands of possible actions. This combined with the myriad of parameters, each protocol having a different format, different regions, different versions, and all the types of inputs we’d like to use, makes it very time consuming.

To add to this difficulty, I am sending legitimate traffic to the API, which in turn can create resources that will cost money (Authors note: This section was written before the aforementioned incident. This was an understatement). As a result, I’ve been watching the billing dashboard like a hawk, and deleting anything that gets created. I’ve also been navigating the AWS Console looking for anything amiss.

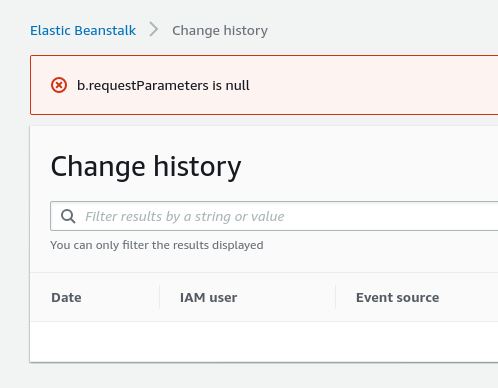

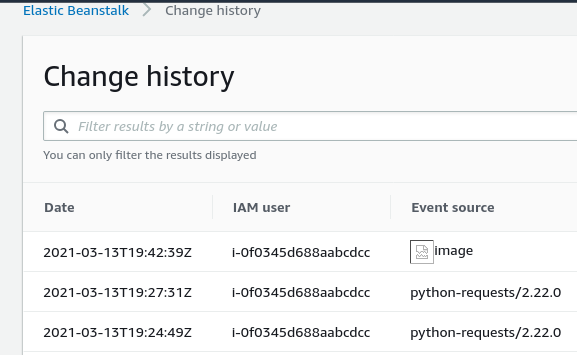

During these checks I stumbled into an error message in the Elastic Beanstalk Change history.

Interesting. At the time, however, I sort of brushed this aside as “weird, you can break a part of the AWS Console” and kept working on the fuzzing library. I even posted the picture to Twitter (if you were one of the two people who liked it before I took it down; Thank you). After a little bit of working, however, it sort of dawned on me, “does that have security implications?” (Yeah, I know right? Master hacker at work).

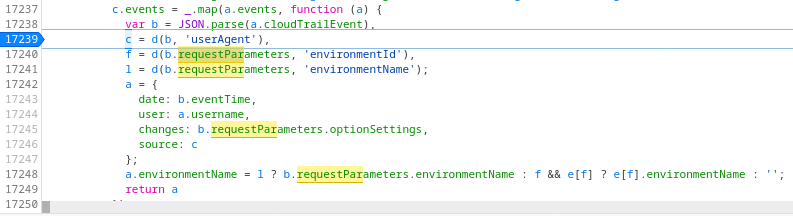

So, what is “b.requestParameters” and why is the AWS Console upset it’s null? Well to find out, I amassed all of the skill and knowledge I’ve built from my years of experience in software development and information security to…….. Ctrl+F for “b.requestParameters” in the JavaScript (again, master hacker at work).

This returned an answer right away. On line 17,240 of beanstalk-xp_en.min.js (That line number comes from the beautified JS output) there was reference to b.requestParameters.

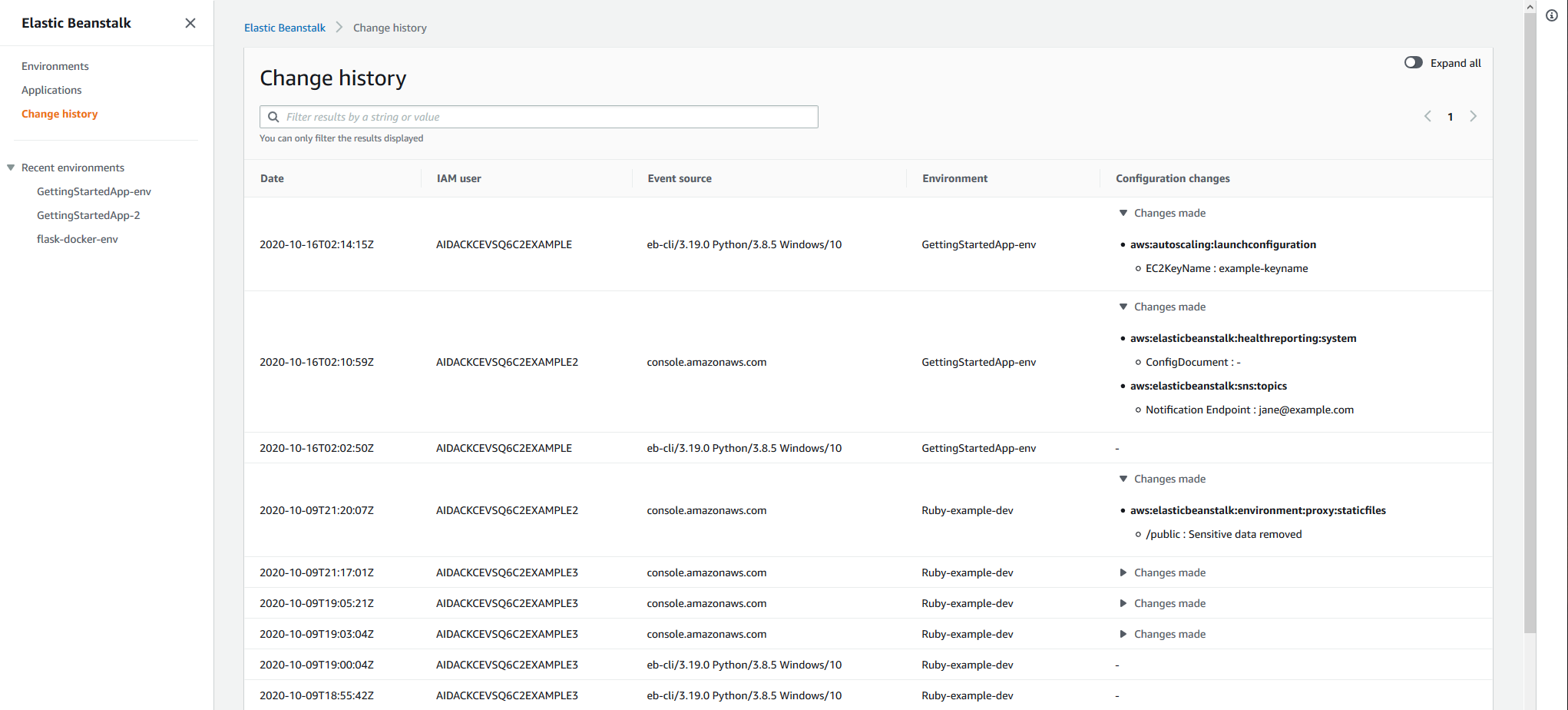

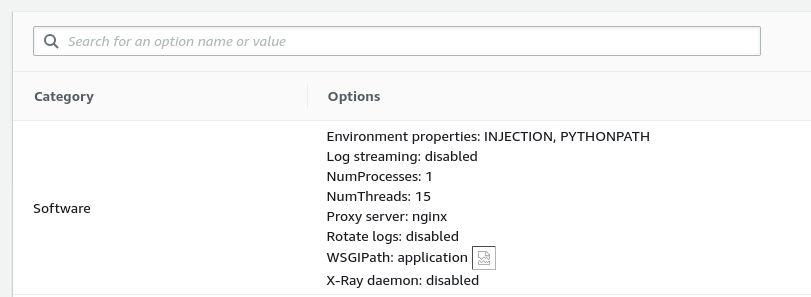

Stepping through with a debugger, it became clear that the Change History page was loading events from CloudTrail and displaying them. For reference, this is how it’s supposed to look (taken from here).

The Change History functionality of Elastic Beanstalk is a pretty new feature (released in January 2021), and allows you to see changes to the configurations of your EB environments.

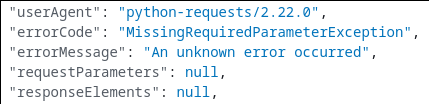

This doesn’t answer the question as to why it’s upset that b.requestParameters is null, what happened? From debugging, it was clear that it was looking for a particular attribute on a CloudTrail event, and the fuzzer hadn’t provided it. Looking in CloudTrail for that particular event, sure enough, I had not provided any parameters when trying the update-environment action, and as a result requestParameters was null.

At last we found our culprit, but what could we do with our new found bug? The next logical step was to explore a little bit.

HTML Injection

From the JavaScript, it was apparent that we had a high degree of control for two values. Those being the user agent and the environmentName. Additionally, it appeared that those values were being inserted directly into the DOM.

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks come to mind, but AWS is normally very good about sanitizing content before rendering it in the browser. This was something I had first hand experience running into when messing around with SSM Agent. And as a result, I figured any malicious content would get sanitized prior to being shown.

To test this I put together a simple payload of a broken image tag (I intentionally set the source to “x”). I like to use this as a test because it gives me a nice visual indicator if it is rendered, otherwise I would just see the encoded value.

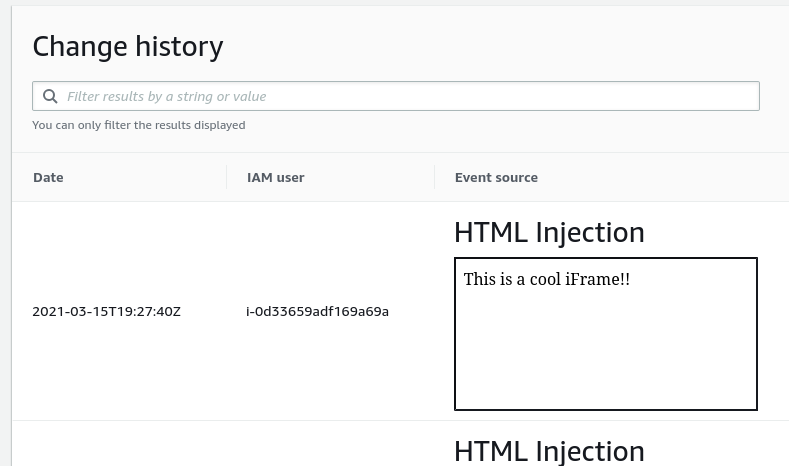

I modified my framework, set the user agent to the payload, hit send and waited. After waiting 10 minutes I refreshed the console and was dumbstruck.

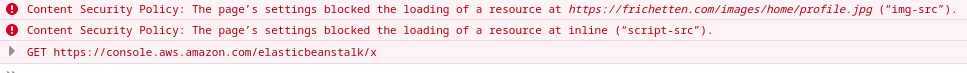

That is valid HTML injection in the AWS Console! The next step, would XSS work? Changed the payload, sent it, and waited a few minutes. Bad news: no JavaScript execution. Reason? the Content Security Policy (CSP) blocked me. If you’re not familiar, you can think of a CSP as a guide to where your browser can load certain resources. JavaScript can load from some domains, fonts can load from different ones, etc.

While a CSP doesn’t mitigate the cause of cross-site scripting attacks, it can mitigate the impact. In this case, the CSP blocked in-line scripts, which made my XSS payload fail.

Looking through the CSP for the console I couldn’t find a way around it. That left us with HTML injection which was a bit disappointing. Could you do some kind of obtuse phishing or social engineering scheme? Yeah maybe. It’s neat, but only in the context that it was found in the AWS Console. I think most realistically you could try and insert an “error” message with a link and try to trick someone that way.

What is kind of interesting was that you only needed valid credentials associated with the account for this to work. Those credentials did NOT need Elastic Beanstalk or CloudTrail permissions. This Change History dashboard would load failed attempts as well. So, even if you had ZERO permissions on a role or user, your attempts to update the Elastic Beanstalk environment would show up.

Iframe Injection

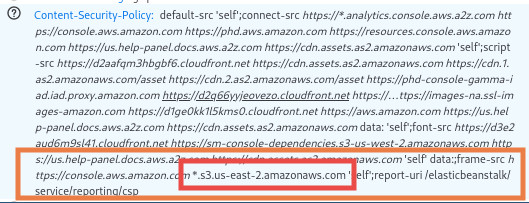

Not seeing a way around the CSP, I reached out to some friends for ideas. While chatting with my friend Chris (check out his blog at schneidersec.com) he noticed something interesting under the iframe section.

The Content Security Policy allowed you to load iframes from an S3 bucket in the same region as the console was set to. We were both surprised at that, couldn’t you just create your own bucket and host HTML? We didn’t see why not, so I created an S3 bucket, put some HTML and changed my payload to create an iframe. That resulted in this:

Indeed you can load the iframe from an S3 bucket!

Submitting to AWS

Not seeing an obvious way to get past the CSP I settled with HTML/iframe injection. Was it cool? Sure, I mean any vuln in the AWS Console is neat, but HTML injection is fluff for a pentest report. Either way, I sent an email over to the AWS Vulnerability Disclosure program along with some screenshots, and a proof of concept (Python script to stick an HTML payload in the user-agent for the update-environment API call).

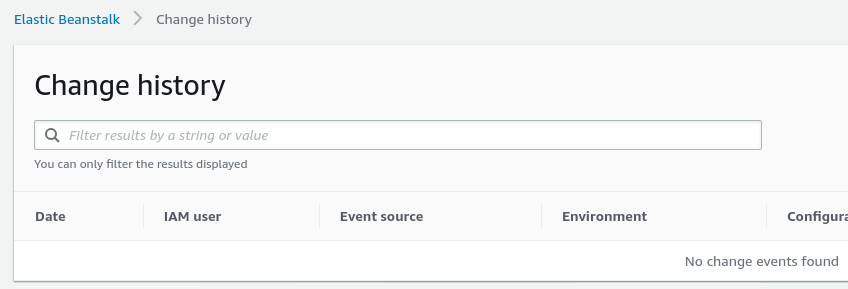

The AWS Security Team responded promptly and said they forwarded the information on to the service team. From here, I waited about two weeks and noticed that I no longer had any events in the Change History page. “Weird”, I thought, “maybe they were just old and dropped off”? So I created some new CloudTrail events and they still didn’t show up.

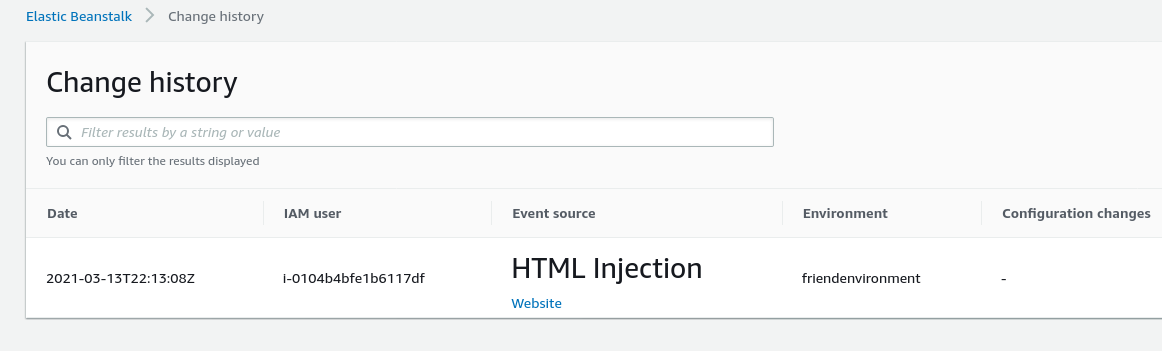

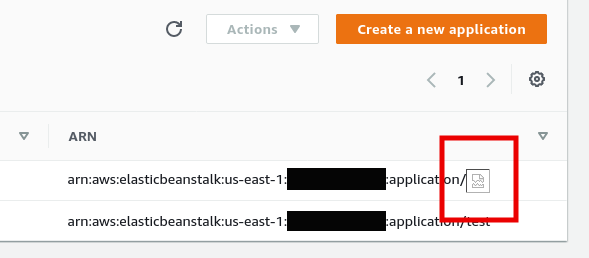

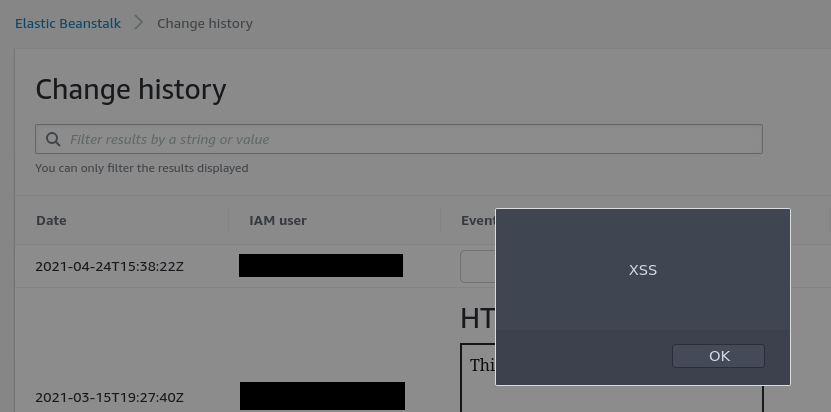

“Maybe they have validation on events now? Either to check for malicious input, or that it affects an existing environment?”. I could tell that the JavaScript responsible for building the table had been modified, but it was minified and diffing the old and the new looked to be too time consuming to pursue. So I created a legitimate Elastic Beanstalk application and environment. As I was doing this, I wanted to poke around and see if any other fields were susceptible to HTML Injection, and indeed there were a few. A couple examples:

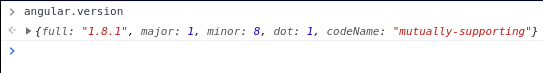

In the interest of being helpful (and hopefully not annoying) I sent another email over to AWS with some screenshots. Disappointed that I couldn’t get the Change History to populate again, even with a real application, I started cleaning up. It was at this time that I had the thought, “What version of Angular does this use”? I quickly found out it didn’t. It used AngularJS.

Template Injection

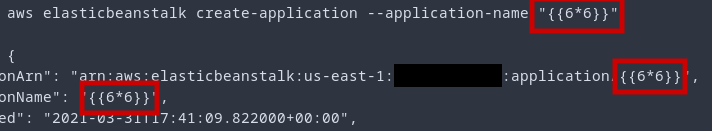

The realization that the page was using AngularJS introduces another type of injection attack we can try, client-side template injection. Template injection attacks occur when an adversary can supply their own template language inputs. This results in those inputs being evaluated in the user’s browser. For example (depending upon the template format) you can insert {{ 2+2 }} and this will evaluate to 4.

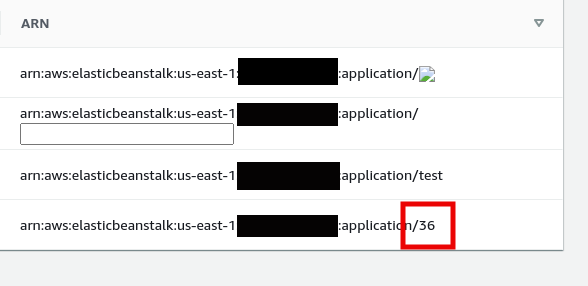

After being sufficiently disappointed in myself for not realizing the AngularJS situation earlier, I created an application with the name of a template and refreshed the browser.

We have confirmed it is susceptible to template injection, but where can we go from here? The good news is that Gareth Heyes of PortSwigger has done some tremendous research in this area (1,2).

In short, we can leverage the template injection as a method to execute arbitrary JavaScript and get Cross-Site Scripting! Previously, this required some work to escape the Angular expression sandbox, however, in AngularJS 1.6 the sandbox was removed. Since we were working with 1.8.1, we didn’t have to worry about it and instead we could use the following payload (taken from here).

{{constructor.constructor('alert(1)')()}}This would allow us to run the traditional alert XSS payload, but would it get past the Content Security Policy? I wasn’t actually sure.

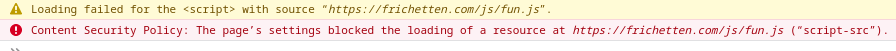

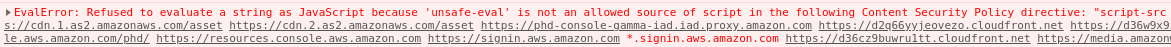

My thought process here was that I’m not injecting a new script tag, I’m just asking AngularJS to evaluate a template expression and because AngularJS is already allowed, wouldn’t it work? This isn’t really inline evaluation right? So I sent the payload and reloaded the screen to be greeted with this nastygram.

Foiled again! Even if we ask AngularJS to evaluate a template it won’t get us XSS. Is there any way we can get around this Content Security Policy?

Bypassing the CSP

The amazing thing is that AngularJS can be used to bypass the CSP! The methodology to do so is roughly equivalent to the idea I had in mind, except rather than injecting a template, we are going to inject HTML. Wait, isn’t that going backwards? You’ll see :)

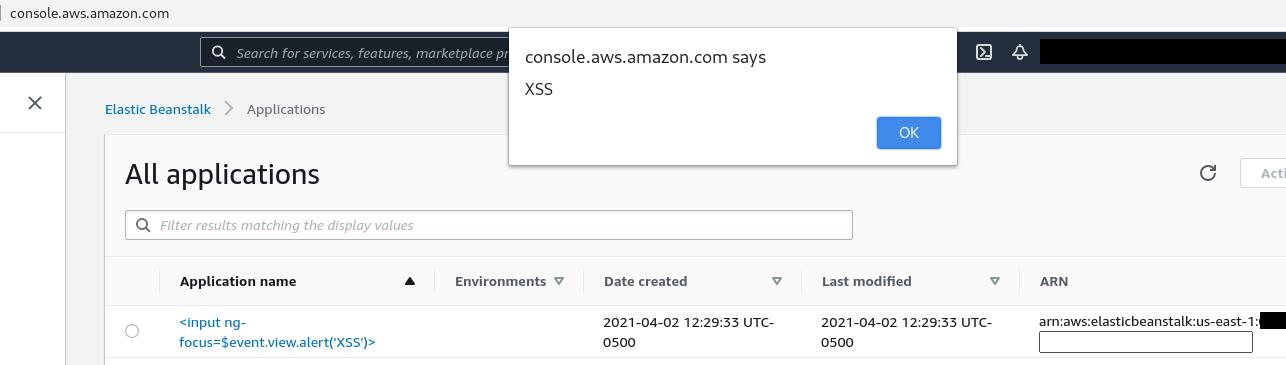

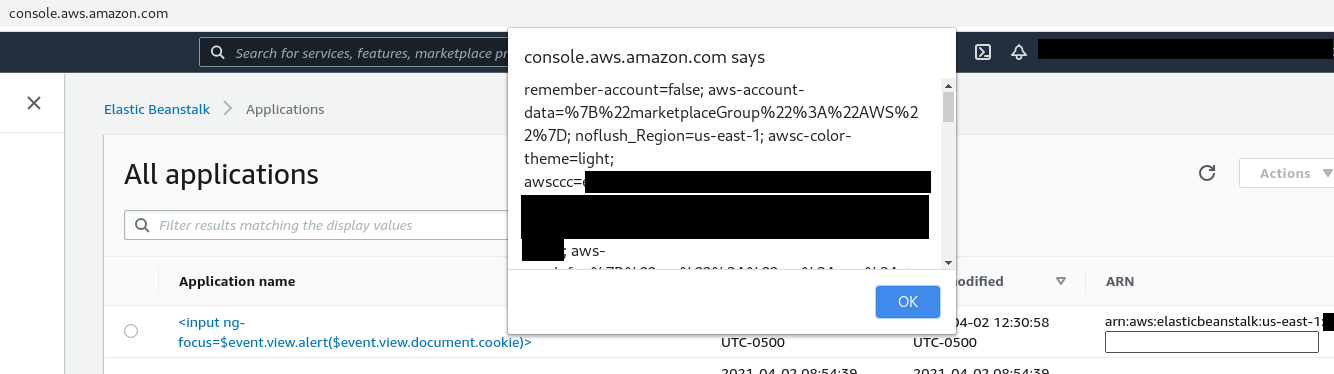

Thanks to some incredible research, again by Gareth Heyes, we cause AngularJS to evaluate JavaScript via directives. After some fiddling I came up with the following payload.

<input ng-focus=$event.view.alert('XSS')>This would leverage the ng-focus directive to launch JavaScript. The $event.view variable would provide us access to all the normal JavaScript functionality that we’d need. So I created an application with that name, refreshed the page, and…

Mission Accomplished! Take that CSP! Victory screech!

After checking that I wasn’t hallucinating, I took some screenshots and sent them off to AWS.

Closing Thoughts

There are a couple things I’d like to point out about this. The first was that I think this is a very interesting attack scenario, potentially going from API access to trying to attack users via the AWS Console. To be clear, this is a VERY rare circumstance. To my knowledge (and Google searching), there was only one other XSS bug found in the AWS Console and disclosed publicly. This is definitely not the kind of thing your average pentest consultancy can whip up on an engagement. But, for a sufficiently sophisticated adversary, in the right situation it could be very handy.

In particular, I think it was super interesting that we could have potentially set XSS in the Change History without any sort of permissions. A hypothetical attack scenario could have been: land on an EC2 instance -> identify Elastic Beanstalk is being used via Resource-Based Policies and detecting the service-linked role for it -> send payload as a role without EB or CloudTrail permissions -> wait -> profit.

I’m not sure why the Change History appeared to not be functioning for a period of time. It has eventually come back and I was able to prove I could get XSS in it (see above screenshot).

Finally, a bit of advice for security researchers; I definitely understand the excitement to submit the bug you found as quickly as possible. What if somebody else finds it and submits it first? What if it gets patched in the next 30 minutes!? While, yes, it is possible for two people to simultaneously discover the same bug, and it is possible that thing you found will be patched before you can inform the developers, it’s not likely to happen. Instead, it’s better to sit on it, think about it all the way through (CHECK THE VERSION OF ANGULAR), and only report it once you are certain you’ve taken it as far as possible.