Intercept SSM Agent Communications

January 27, 2021

The following is some research I’ve done on leveraging SSM Agent communications for post-exploitation. Please note, I am not claiming that these are vulnerabilities with the SSM Agent or SSM.

Due to how SSM handles authentication, if you can get access to the IAM credentials of an EC2 instance you can intercept EC2 messages and SSM sessions. This means even a low privilege user can intercept these communications. While this is not necessarily a novel idea (this is literally how the SSM Agent works), I had not seen anyone leveraging this for malicious purposes (please let me know if I’m missing prior research).

With this article I’d like to explain how someone could intercept these communications, alter them, or prevent the owner from accessing the EC2 instance entirely. Additionally this may help explain how parts of the SSM Agent operate on a low level. From an impact perspective, if someone gains access to your EC2 instance (even a low privileged user), they can effectively prevent you from communicating with it, snoop on that communication, or send their own responses.

As always, proof of concept scripts can be found here.

Intercept EC2 Messages

If you’ve ever intercepted the traffic of the SSM Agent, you’ll notice that it will constantly call ec2messages:GetMessages. By default the agent will do this constantly, keeping the connection open for approximately 20 seconds. During this 20 second interval, the agent is listening for messages. If it receives one, such as when someone calls ssm:SendCommand, it will receive the message via this open connection.

This behavior introduces an interesting question. If I get code execution on the EC2 instance (or otherwise get access to its IAM creds) could we do this ourselves and listen for messages? Well, yes.

We can call ec2messages:GetMessages on our own, and this will allow us to intercept EC2 messages coming to the instance. There is a slight problem though. The SSM Agent will make these connections approximately every 20 seconds. What happens if there are two competing connections? AWS will only respond to the connection that is the “newest”. As a result, if the SSM Agent goes first, we can create a new connection on top of it and intercept the message.

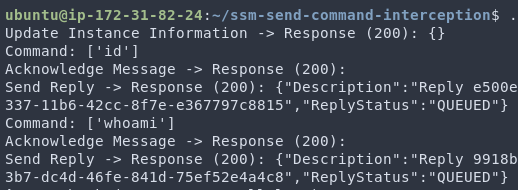

We can ensure we have the newest connection (or very close to it) by repeatedly opening new connections over and over again. Through this method, we ensure that we will always be the newest one, and ensure we can intercept EC2 messages. To test this idea, I created a simple proof of concept that will listen for send-command messages and steal the command.

Another nice feature of this is that we can reply with whatever response we’d like. For example we provide a ‘Success’ and return a fun message. Here is an example from the proof of concept.

Intercept SSM Sessions

The implementation of EC2 messages is relatively simple. You check if you have a message, perform the action, and respond. Unfortunately SSM Sessions are much more complicated. This involves multiple web socket connections, a unique binary protocol, and more. The following is a summation of the relevant concepts.

Shortly after the SSM Agent starts up, it will create a WebSocket connection back to AWS. This connection is the control channel, and is responsible for listening for connections. When a user tries to start an SSM session (ssm:StartSession), the control channel will receive the request and will spawn a data channel. The data channel is responsible for the actual communication from the user to the EC2 instance.

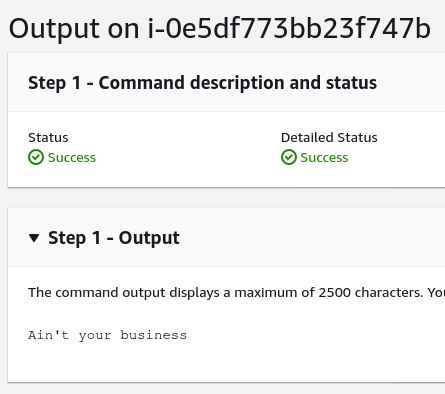

The communication that takes place between the clients is a binary protocol specifically for this purpose. Thankfully, the source code for the SSM Agent is available here, and we can just look up the specification for it. It looks something like this.

From an abuse perspective, intercepting SSM Sessions is more reliable than EC2 messages. The reason for this is that the control channels are long lived, and just like with EC2 messages AWS will only communicate with the newest one. As a result, we can create our own control channel and listen for incoming sessions. Using the SSM Agent source code, we can craft the messages in the binary format (if you look at my proof of concept, you’ll notice I’ve literally just translated the Go to Python), and interact with the session.

Because of this we can do things like the following.

Alternatively, we could do things like stealing the commands and supplying our own output. For example, trying to snoop on credentials being passed to the machine.