A Look at AWS API Protocols

January 23, 2023

Recently I’ve been diving back into vulnerability research on AWS in my free time. As a part of this, I’ve been building some tooling to save time as well as documenting some concepts along the way. With this blog post I’ll discuss the concept of a protocol in the AWS API and how it impacts the structure of an AWS API request.

Much of the content for this article comes from the Smithy AWS Protocol specifications, helpful comments and code in the SDKs, and my own personal experience.

The structure of an AWS API call

Many AWS security fans may be aware that all requests to the AWS API are signed using a signing protocol called Signature Version 4 (SIGv4). This protocol has a number of security benefits designed to mitigate the risk of replay attacks, prevent tampering in transit, and more.

While SIGv4 signs all requests, it is not prescriptive in terms of the structure of the request. This message can be of any HTTP Verb (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, etc), of any Content-Type, and can send information in different forms such as JSON, XML, etc. As a result, AWS APIs make calls in a variety of different formats.

If you were to intercept requests from, for example, the AWS CLI, you may think they are randomly formatted. As it turns out though, there is some method to this madness in the form of the API’s “protocol”. The protocol dictates the overall structure of the API requests for a particular service. As of today, all public AWS services fall into one of five protocols; ec2, query, json, rest-json, and rest-xml.*

The easiest way to determine the type of protocol a service uses would be to see its service-2.json file in botocore. For example, Lambda uses the rest-json protocol:

{

"version":"2.0",

"metadata":{

"apiVersion":"2015-03-31",

"endpointPrefix":"lambda",

"protocol":"rest-json",

"serviceFullName":"AWS Lambda",

"serviceId":"Lambda",

"signatureVersion":"v4",

"uid":"lambda-2015-03-31"

},

…snip…The protocol of the API will determine the structure of the API request. For example, the Amazon Elastic Container Service (ECS) using the json protocol. An API request for the ECS service could look like the following (with heavy editing to highlight certain points):

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: ecs.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

X-Amz-Target: AmazonEC2ContainerServiceV20141113.ListClusters

Content-Type: application/x-amz-json-1.1

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 Credential=ASIAEXAMPLEEXAMPLEEX/20230121/us-east-1/ecs/aws4_request, SignedHeaders=content-type;host;x-amz-date;x-amz-security-token;x-amz-target,...

{}The most notable features of the json protocol are the X-Amz-Target header, which specifies the action to be performed, and the Content-Type header, which specifies which json version to use.

If we compare this with something like IAM, which uses the query protocol we see a much different structure:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: iam.amazonaws.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=utf-8

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 Credential=ASIAEXAMPLEEXAMPLEEX/20230122/us-east-1/iam/aws4_request, SignedHeaders=content-type;host;x-amz-date;x-amz-security-token,...

Action=ListUsers&Version=2010-05-08Here, there is no X-Amz-Target header. It is instead passed as the Action parameter in the body of the request, which notably does not use JSON.

If you’d like to compare similarities of the other protocols, I’d encourage you to intercept CLI traffic and inspect it yourself.

Cross-Protocol Requests

So far we’re addressed that some AWS services communicate using specific protocols. What is interesting to note however, is that some services can actually speak multiple protocols. For example, ECS, which we demonstrated above uses the json protocol, can actually use query as well.

POST / HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=utf-8

Host: ecs.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 Credential=ASIAQEPLEVBZIQ24U2FR/20230122/us-east-1/ecs/aws4_request, SignedHeaders=content-type;host;x-amz-date;x-amz-security-token,...

Action=ListClusters&Version=2014-11-13The request above (un-edited) will return a successful response from the AWS API. Not every service can speak every protocol and, as far as I know, there is no way to determine ahead of time which services are compatible with which protocol.

You may be wondering, “Nick, this is neat, but who cares? Why does the protocol the service uses matter”? Good question. The primary reason I’m interested in this topic is because if a particular protocol has a vulnerability in it, we can abuse large numbers of AWS services at once. And, if we can identify services that work with multiple protocols (I.E cross-protocol requests) we can expand that list even more.

AWS API Protocol Vulnerabilities

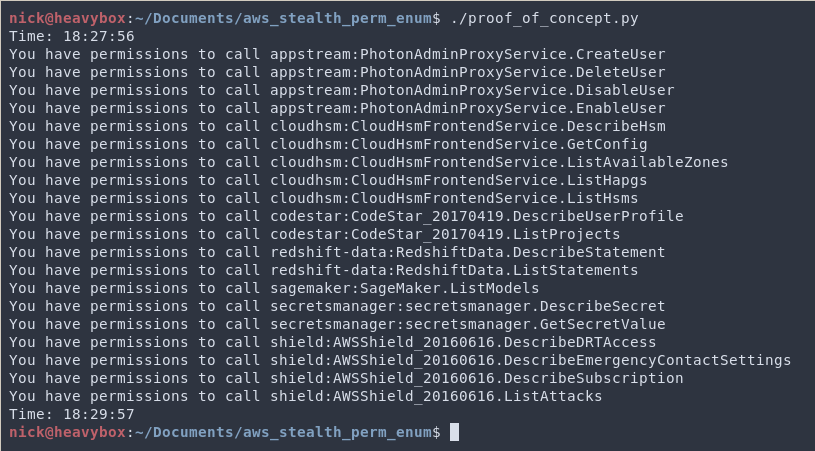

What do I mean by “protocol vulnerabilities”? These would be vulnerabilities related to how a particular protocol is parsed and evaluated by the AWS backend. For example, back in 2020 I found a vulnerability in the json 1.1 protocol which allowed me to enumerate if I did or did not have privileges to perform a specific action, without logging to CloudTrail.

This was done by setting an incorrect Content-Type header, and seeing the differences in responses. Specifically, using application/x-amz-json-1.0 on 1.1 compatible services. This vulnerability was incredibly powerful from a post-exploitation perspective because it enabled adversaries to discover a large number of permissions they may have WITHOUT logging to CloudTrail. This would enable adversaries to perform that enumeration without leaving a trace, when normally it would get them caught.

Due to the complexity of the various protocols, I think it is fertile ground for future research and likely more vulnerabilities to emerge. If you’re in the AWS security research scene, I encourage you to poke around to see what you find. You never know what may be lurking.

- Technically there are 6 because the json protocol has two versions (1.0 and 1.1) however, due to how similar they are, I’m considering them as a single protocol. This decision is also largely supported by the source code of the botocore library as well.